Foreword: Why activity theory?

This chapter is about a theory that was developed decades ago. Some of the basic ideas of the theory were formulated before the word "computer" was ever invented. Then why does the Encyclopaedia of Human-Computer Interaction feature a chapter on the theory? In other words, Why activity theory?

The question can be answered in two steps.

(a) Why activity?

Activity is currently one of the most fundamental concepts in HCI research (Moran, 2006). Early HCI was predominantly concerned with understanding and supporting tasks, which people do to achieve clear predetermined goals (such as making certain changes in a document). The issues of why a person carries out a task and what the task means to the person were typically outside the scope of analysis, evaluation, and design. However, with interactive technology becoming a part of our everyday environments the focus on tasks proved to be insufficient. Understanding and designing technology in the context of purposeful, meaningful activities is now a central concern of HCI research and practice. Virtually all significant recent developments in interactive technologies — think about, for instance, social media, smartphones, and bookreaders — owe their success to helping us live fuller lives rather than merely supporting new types of tasks.

(b) Why activity theory?

Most people have an intuitive understanding of what activities are. Is there any need for a theory here?

A problem with intuitive, commonsense notions of activity is that they can be different for different people. In addition, they may be not specific enough. How to distinguish activities from non-activities? Can activities be broken down into smaller units? What role does technology play in human activity? To answer these and other similar questions HCI needs a more elaborated concept of activity. Such concept is offered by activity theory, discussed in this chapter.

16.1 Introduction

Activity theory is a conceptual framework originating from the socio-cultural tradition in Russian psychology. The foundational concept of the framework is “activity”, which is understood as purposeful, transformative, and developing interaction between actors (“subjects”) and the world (“objects”). The framework was originally developed by the Russian psychologist Aleksei Leontiev (footnote 1) (Leontiev 1978; Leontiev 1981). A version of activity theory, based on Leontiev’s framework, was proposed in the 1980s by the Finnish educational researcher Yrjö Engeström (1987). Currently, both Leontiev’s and Engeström’s variants of activity theory, as well as their combinations, are being widely used interdisciplinarily, not only in psychology, but also in a range of other fields, including education, organizational learning, and cultural studies.

Since the early 1990s, activity theory has been a visible landmark of the theoretical landscape of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). In the last two decades, activity theory, along with some other frameworks, such as distributed cognition and phenomenology, has established itself as a leading post-cognitivist approach in HCI and interaction design (e.g., Bødker, 1991; Nardi, 1996a; Bertelsen and Bødker, 2003; Kaptelinin et al., 2003; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006). Carroll 2011 observes that: “Information processing psychology and laboratory user studies, once the kernel of HCI research, became important, but niche areas. The most canonical theory-base in HCI now is socio-cultural, Activity Theory.”

This chapter discusses the past, present, and future of activity theory as a theoretical approach in HCI. It starts with a brief introduction to the basic concepts and principles of activity theory, continues to describe its key contributions to research in HCI and interaction design, and concludes with reflections on challenges and prospects for further development of the approach.

The chapter is not intended to be a comprehensive exposition of the framework and its uses in HCI. More detailed discussions of activity theory concepts and applications in the context of HCI research can be found for instance, in Bødker (1991), Nardi (1996a), Engeström et al. (1999), Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006), and Kaptelinin and Nardi (2012)).

16.2 Brief overview of activity theory

16.2.1 Historical roots and underlying assumptions

The immediate conceptual roots of activity theory can be traced to Russian/Soviet psychology of the 1920s and 1930s (footnote 2). During that time theoretical explorations in Russian psychology were heavily influenced by Marxist philosophy. A collective effort of a number of prominent psychologists, most notably Lev Vygotsky and Sergey Rubinshtein—which effort also involved much disagreement and even open conflicts—gave rise to a socio-cultural perspective (understood in a broad sense) in Russian psychology (e.g., Vygotsky, 1978; Rubinshtein, 1946; Rubinshtein 1986).

The main conceptual thrust of the socio-cultural perspective was to overcome the divide between, on the one hand, human mind, and on the other hand, culture and society. As opposed to most psychological frameworks of that time, the perspective considered culture and society generative forces, “responsible” for the very production of human mind, rather than external factors, however important, that merely constitute conditions for the functioning of the mind without changing its basic nature.

The work based on the socio-cultural perspective produced a number of fundamental insights. Some of the most important contributions were as follows:

Vygotsky’s universal law of development, according to which human mental functions first emerge as distributed between the person and other people (i.e., “inter-psychological ”) and only then as individually mastered by the person himself or herself (i.e., “intra-psychological”), and

Rubinshtein’s principle of “unity and inseparability of consciousness and activity”, according to which human conscious experience and human acting in the world, the internal and the external, are closely interconnected and mutually determine one another.

Aleksei Leontiev’s activity theory (footnote 3) emerged as an outgrowth of the socio-cultural perspective. The theory employs a number of ideas developed by Vygotsky, Leontiev’s mentor and friend. It is also strongly influenced by the work of Rubinshtein, a major figure in Russian psychology and a long-time colleague of Leontiev’s (Brushlinsky and Aboulhanova-Slavskaya, 2000). Arguably, activity theory also features some other important influences which are more difficult to discern, such as the framework developed by Mikhail Basov (Basov, 1991). The basic assumptions of activity theory are the same as those underlying the socio-cultural perspective in general: namely, the assumptions of the social nature of human mind and inseparability of human mind and activity.

At the same time, Leontiev’s activity theory is not a simple imprint of all these influences. As discussed below, while the theory incorporates a variety of ideas developed by Vygotsky, Rubinshstein, and others, these ideas have been revised and elaborated upon by Leontiev to form his own distinct and consistent conceptual framework.

Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Author/Copyright holder: Psyberia.ru. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 16.1 A-B-C: From top to bottom: Aleksei Nikolaevich Leontiev, Lev Semenovich Vygotsky, and Sergey Leonidovich Rubinshtein

16.3 Basic concepts and principles of Leontiev's framework

16.3.1 The concept of 'activity'

Activity, in a broad sense, is an interaction of the actor (e.g., a human being) with the world. The interaction, according to activity theory terminology, is described as a process relating the subject (S) and the object (O). A common way to represent activity is “S ⇔ O”. There are two key aspects differentiating activity from other types of interaction: (a) subjects of activities have needs, which should be met through an interaction with the world, and (b) activities and their subjects mutually determine one another; or, more generally, activities are generative forces that transform both subjects and objects.

Subjects have needs. Activity is understood as a “unit of life” of a material subject existing in the objective world. Subjects have their own needs and, in order to survive, have to carry out activities, that is, interact with objects of the world to meet their needs. Leontiev’s analysis was mostly concerned with activities of individual human beings, but the notion of “subject” is not limited to individual humans. Other types of entities, such as animals, teams, and organizations can also have need-based agency and, therefore, be subjects of activities (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006).

Activities and their subjects mutually determine one another. It is immediately obvious that activities are influenced by the attributes of subjects and objects. Consider a simple example. Undoubtedly, whether or not a person can solve a math problem depends on the nature of the problem (e.g., how difficult it is) and the person’s abilities and skills (i.e., how good the person is at math). In the long run, however, the opposite is also true: both the object and the subject are over time transformed by the activity. It is apparent, for instance, that a person’s math skills are a result of previous experience: they have developed through solving math problems in the past. In other words, while it is true that a person’s math abilities determine how the person solves math problems, it is also true that solving math problems determine the person’s math abilities. Therefore, subjects do not only express themselves in their activities; in a very real sense they are produced by the activities (cf. Rubinshtein, 1986).

Mind and activity: Leontiev vs. Rubinshtein

Leontiev extends and develops Rubinshtein’s principle of unity and inseparability of consciousness and activity in three respects. First, Leontiev states that psychological studies should not be focusing only on the “psychological aspect or facet of activity” (as suggested by Rubinshtein), such as the relationship between activity and subjective experiences. Instead, he maintained that the relevance of activity to psychology is of a more general nature: activity is of fundamental importance to psychology because of its special function, the function of placing the subject in the objective reality and transforming this reality into a form of subjectivity (Leontiev, 1978). Second, as discussed below, Leontiev’s analysis focuses on both conscious and unconscious mental phenomena. Third and finally, Leontiev offered a number of more concrete insights about the relationship between mind and activity, most notably the idea of structural similarity between internal and external processes (Leontiev, 1978; Leontiev, 1981).

16.3.2 Basic principles

The main ideas and assumptions of activity theory, outlined above, have been elaborated by Leontiev into a set of more specific notions, claims, and arguments. A common problem with interpreting Leontiev’s texts is that they often reflect the unfolding logic of his conceptual explorations rather than provide a systematic overview of the logical structure of the framework as a whole. There have been several attempts to translate the representation of Leontiev’s framework, as it is described in his texts, into a structured set of distinct principles. Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006), building on Wertsch (1981), identify the following principles:

16.3.2.1 Object-orientedness

This principle (which bears some similarity to phenomenology’s notion of “intentionality” - see Dourish, 2001) is directly related to the very concept of activity as a “subject-object” relationship. Why is subjects’ interaction with the world defined in terms of interacting with objects? The explanation, offered by the principle of object-orientedness, is as follows. The world is structured; it comprises discrete objectively existing entities, that is, objects. Subjects’ interaction with the world is also structured; it is organized around the objects. Objects have their “objective” meanings, determined by their relationship with other entities existing in the world (including the subject). In order to meet their needs, the subject has to reveal the objective meaning of the objects, at least partly, and act accordingly.

Therefore, the object of activity has two facets, it should be understood:

First, in its independent existence as subordinating to itself and transforming the activity of the subject

Second, as an image of the object, as a product of its property of psychological reflection that is realized as an activity of the subject and cannot exist otherwise (Leontiev, 1978).

These two facets do not necessarily always coincide. They are dynamically aligned in the unfolding “subject-object” interaction. The alignment involves a double transition: the subject’s activity is subordinated to properties of the object which gives rise to new activity structures; in turn, new activity structures bring about new subjective phenomena, such as a more developed image of the object. For instance, a tourist wandering around an area may initially have a vague idea about the area and simply follow the constraints and possibilities provided by the environment. Over time, emerging patterns of walking may result in a development of an elaborated cognitive map of the area.

The principle of object-orientedness applies differently to animals and human beings. Animals live in a structured world of natural objects which are material and mostly have direct positive or negative meanings and values, provide affordances for action, and so forth. Human beings live in a predominantly man-made world, where objects are not necessarily physical things: they can be intangible, but they can still be considered “objects” as long as they objectively exist in the world. For instance, the objects of learning a new language or making a company profitable are impossible to touch, physically weigh, or measure with a ruler. However, the grammatical structure of a language or profit margin of a company does not exist merely in a person’s imagination. Rather, they are “facts of life”, which need to be faced and dealt with. “Objective” is understood in activity theory in a broad sense as including not only the properties of things that can be directly registered with physical instruments, but also socially and culturally defined properties.

Therefore, the principle of object-orientedness states that all human activities are directed toward their objects and are differentiated from one another by their respective objects. Objects motivate and direct activities, around them activities are coordinated, and in them activities are crystallized when the activities are complete. Analysis of objects is therefore a necessary requirement for understanding human activities, both individual and collective ones.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation).

Figure 16.2: Hierarchical structure of activity

Lost in translation: “Predmet” vs. “objekt”

There is a language problem, which makes an adequate translation of Leontiev’s notion of “object” from Russian to English somewhat complicated. In Russian there are two words which have similar but distinct meanings: “objekt” and “predmet”. Both refer to objectively existing entities, but the notion of “predmet” typically also implies a relevance of the entity in question to certain human purposes or interests (footnote 4). Similar linguistic distinctions can be found in German and some other languages. Leontiev deliberately referred to the object of activity as “predmet” rather than “objekt”. However, this distinction is usually lost in English translation since both words are translated as “object”. This linguistic problem is a likely reason why the emergence of objects of activities-the dynamics of “just objects” becoming involved in activities and acquiring the status of “objects of activities”, and vice versa-have not so far received the attention they deserve in concrete studies informed by activity theory.

16.3.2.2 Hierarchical structure of activity

Human activities, according to Leontiev, are units of life which are organized into three hierarchical layers (see Figure 2). The top layer is the activity itself, which is oriented toward a motive, corresponding to a certain need. The motive is the object that the subject ultimately needs to attain. For instance, in some cultural contexts people reaching a certain age need to learn how to drive a car (and get a driver’s license); it is a general prerequisite of being a fully functional member of society. Learning how to drive a car is an activity which is organized as a multi-layer system of sub-units directed at getting a driver’s license. Actions are conscious processes directed at goals which must be undertaken to fulfil the object. Goals can be decomposed into sub-goals, sub-sub-goals, and so forth. For instance, one may decide to enroll in a driving school, purchase instructional materials, make a schedule of theoretical lessons and practice sessions, etc. Actions are implemented through lower-level units of activity, called operations. Operations are routine processes providing an adjustment of an action to the ongoing situation. They are oriented toward the conditions under which the subject is trying to attain a goal. People are typically not aware of their operations. For instance, a driving school student taking notes during a lecture might be fully concentrated on traffic rules rather than the process of writing. Operations emerge in two ways. First, an operation can be a result of step-by-step automatization of an originally conscious action (e.g., over time, the action of changing lanes may transform into a routine operation, which does not require conscious control). When such operations fail, they are often transformed into conscious actions again. Second, an operation can be a result of “improvisation”, a spontaneous adjustment of an action on the fly (e.g., in an emergency situation the driver may act “instinctively”, without thinking).

The three-layer model only applies to human activities. Complex relationships between motives (i.e., what motivates the activity) and goals (i.e., what directs the activity) is a characteristic feature of humans. While animals usually act directly toward the objects that motivate them (e.g., food), humans often attain their motives by directing their efforts to other things (e.g., however hungry, people usually grab a menu, rather than the first available food, upon entering a restaurant). This feature, according to Leontiev, is a product of the complex social organization of human life. In particular, the emergence of division of labour entails the need for some people to focus on objects, different from the ones that actually meet a certain need. For instance, the actions of primordial hunters who scare the game away (i.e., “beaters”) may look paradoxical if one does not know that the game is directed toward another group of hunters, waiting in the ambush (i.e., “ambushers”). Once the feature of the social organization of life, the dissociation between motivating objects (motives) and directing objects (goals) shapes the structure of individual activities and becomes its characteristic feature, as well (Leontiev, 1981).

Considering human activity as a three-layer system opens up a possibility for a combined analysis of motivational, goal-directed, and operational aspects of human acting in the world, that is, bringing together the issues of Why, What, and How within a consistent conceptual framework (Bødker, 1991). Realizing this possibility in a concrete study may, however, be problematic. Revealing the ultimate motives of a person or the fine-grain structure of automatic operations may prove to be difficult, if not impossible. This limitation of Leontiev’s three-layer model as an analytical tool can be overcome by employing an expansive “actions first” strategy. This strategy involves starting analysis from the actions layer which relatively easily yields itself to qualitative research methods. In particular, people are usually aware of their goals and can report or express them in a certain way. Then the analysis can be expanded both “up”, to progressively higher level goals and, ultimately, motives, and “down”, to sub-goals and operations. The expanding scope of analysis may not cover the entire structure of the activity in question but be sufficient for the purposes of the task at hand (see also Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006).

16.3.2.3 Mediation

Arguably, mediation is the primary dimension along which human beings differ from other animals. It is mediation which has made homo sapiens such a successful species: while we do not have sharp claws and thick fur, we compensate that by employing mediating artefacts, such as hammers, knives, and warm clothes. The effect of complex social organization on the structure of individual human activity, discussed above and illustrated by the case of primordial hunters, is another example of mediation. In fact, the main distinctive features of humans, such as language, society and culture, the production and use of advanced tools, etc., all involve mediation. They represent different aspects of the same phenomenon, that is, the emergence of a complex system of objects and structures, both material and immaterial which serve as mediating means embedded in the interaction between human beings and the world and shaping the interaction.

Activity theory inherits its special interest in mediation from the approach that made the most fundamental impact on Leontiev’s framework - that is, Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology. In cultural-historical psychology mediation is, arguably, the most important concept of all; it serves as the cornerstone of the approach as a whole. Vygotsky proposed that the very nature of human mental processes, as opposed to animals’ mental processes, is defined by mediation. Vygotsky’s ideas concerning mediation were explicitly incorporated into the conceptual framework of activity theory but placed in a somewhat different theoretical context. As opposed to Vygotsky, who was predominantly interested in particular higher mental functions and their ontogenetic development and, therefore, particularly concerned with means that mediate specific mental operations (especially, signs), Leontiev's mainly focussed on means that mediate a purposeful object-oriented activity as a whole.

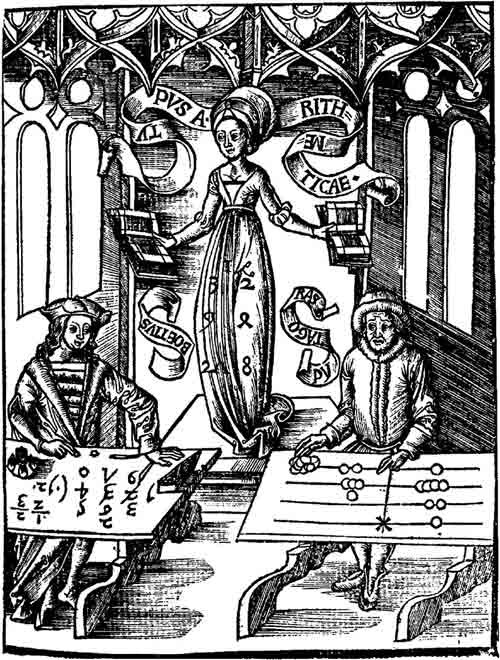

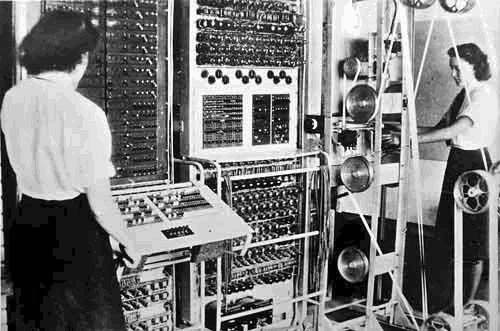

Tool mediation allows for appropriating socially developed forms of acting in the world. Tools reflect the previous experience of other people, which experience is accumulated in the structural properties of tools, such as their shape or material, as well as in the knowledge of how the tool should be used (see Figure 3 to 8). Therefore, the use of tools is a form of accumulation and transmission of social, cultural knowledge. Tools not only shape the external behaviour. As discussed below, through internalization they also influence the mental functioning of individuals. For instance, a person’s cognitive map of a city may depend on whether or not the person is a car driver. Some folklore sayings also suggest that our perception of the world is affected by the tools we are using, e.g.: “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

16.3.2.4 Example of mediation and accumulation of experience over time: Devices for calculation and computation

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Gregor Reisch,1508. Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 16.3: Woodcut of a “Calculating-Table” by Gregor Reisch, 1508. The woodcut shows Arithmetica instructing an algorist and an abacist

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Sergei Frolov and the Soviet Calculators Collection. Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 16.4: Soviet-produced calculator from the Soviet Calculators Collection

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of The United Kingdom Government. Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 16.5: Colossus, the world's first totally electronic programmable computing device, built 1943-1945

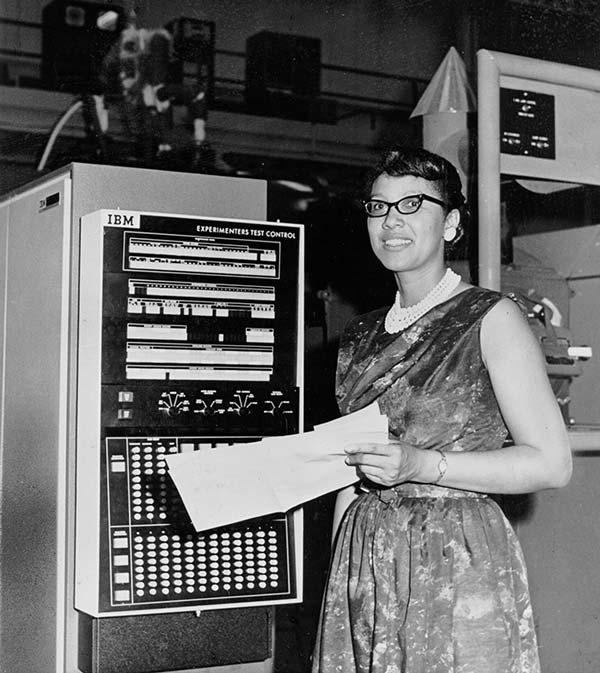

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation).

Figure 16.6: A female “computer”: Melba Roy headed the group of NASA mathematicians who were known as “computers.” They tracked the Echo satellites. Roy's computations helped produce the orbital element timetables by which millions could view the satellite from Earth as it passed overhead

Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 16.7: The Xerox Alto, introduced in 1973, but never commercially produced. The Alto was the predecessor of the Xerox Star, an early “personal computer”, introduced in 1981

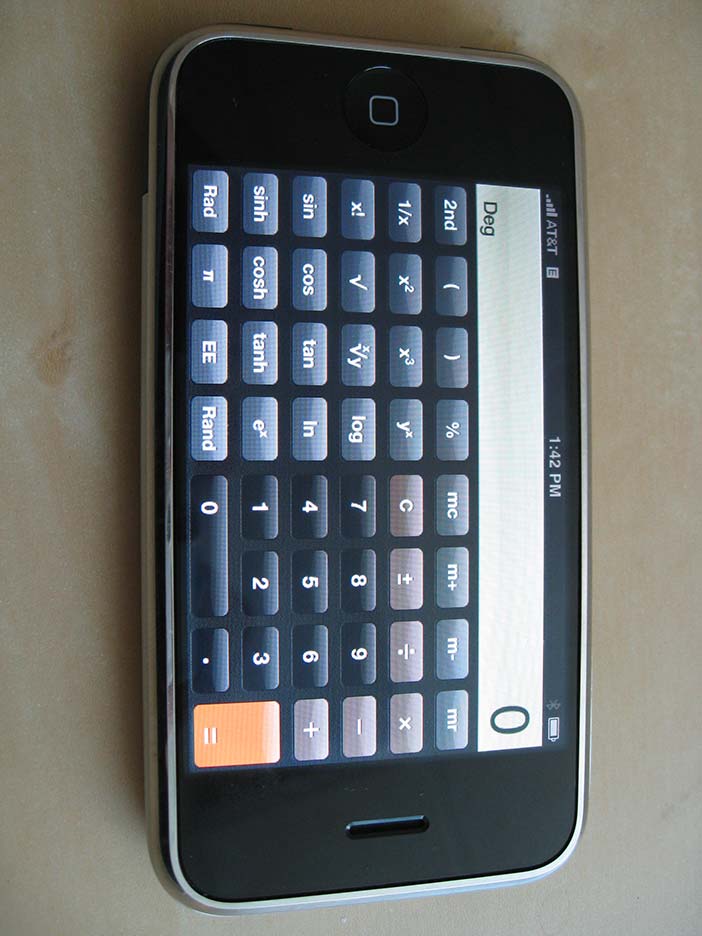

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Jeff Wilcox. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-2 (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Unported).

Figure 16.8: A calculator on an iPhone, anno 2009

16.3.2.5 Internalization and externalization

This principle states that human activities are distributed - and dynamically re-distributed - along the external/internal dimension. Any human activity contains both internal and external components. Sometimes external components are hardly visible: they can be reduced, for instance, to eye movements or even patterns of brain activation, but they are always present. The concepts of internalization and externalization refer to the processes of mutual transformations between internal and external components of an activity.

In the process of internalization external components become internal. For instance, young children often use their fingers to do simple math, but over time the use of fingers typically becomes redundant. An inexperienced driver may speak aloud to remind himself of the “parallel parking” procedure, but the need for speaking aloud is likely to disappear with practice.

The concept of internalization in activity theory is similar to the one proposed in some other frameworks, most notably Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology. Within Vygotsky’s framework the notion of internalization predominantly refers to a step in the development of higher mental functions, at which sign mediation initially emerging in the external plane eventually progresses to the internal plane. In activity theory internalization is used in a broader meaning as any re-distribution of internal and external components of an activity that results in a shift from the external to the internal.

Furthermore, in activity theory internalization is considered as just one type of transition, and providing a full account of the dynamics of activity “...necessarily presupposes the existence of regularly occurring transitions in the opposite direction also, from internal to external activity. “ (Leontiev, 1978). The process, opposite to internalization is externalization - that is, transformation of internal components of an activity into external ones. An example of externalization is sketching a design idea (see Figure 9).

Leontiev observed that in modern forms of work internal and external components of activity are becoming increasingly intertwined: ”Physical work accomplishing a practical transformation of material objects, ever more “intellectualized,” incorporates into itself the carrying out of more complex mental acts; at the same time the work of the contemporary researcher, activity that is specially cognitive, intellectual par excellence, is ever more filled with processes that in their form are external actions” (Leontiev, 1978).

In a similar vein, an activity, which is initially socially distributed, that is, distributed between several people (e.g., driving a car by a person taking a driving lesson, distributed between the learner and driving instructor) can be appropriated by a person (i.e., the learner) and then carried out individually. The opposite process is the transformation of an individual activity into a socially distributed one, e.g., when a person initiates a group project or other people intervene to help an individual to carry out her actions (Cole and Engeström, 1993). The dimensions of internal/external and individual/social are similar to one another in many respects and are closely related. For instance, when an internal activity is externalized, it also affects the individual-collective dimension: for instance, tools and signs employed in externally distributed actions can be shared and thus enable social distribution of the actions.

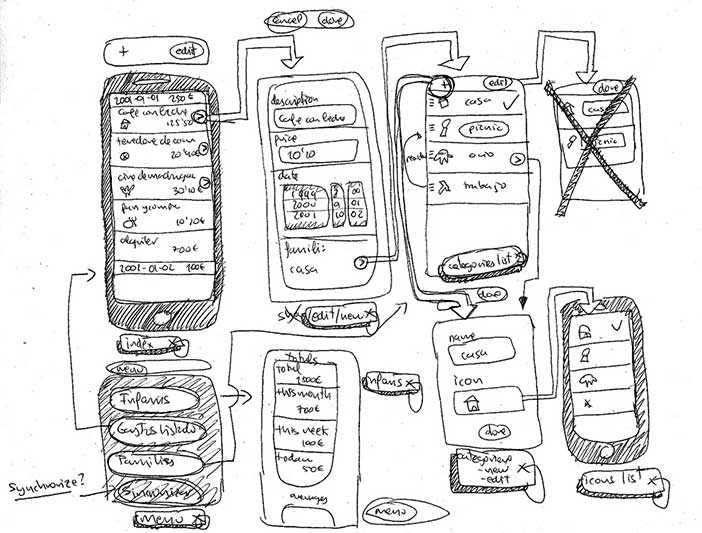

Author/Copyright holder: Fernando Guillen. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 16.9: Externalization: Sketching a user interface idea

16.3.2.6 Development

Finally, activity theory requires that activities always be analysed in the context of development. Development in activity theory is both an object of study and research strategy. As an object of study, development constitutes a complex phenomenon that can be analysed at different levels. Examples of the levels of analysis include studying the development of various forms of animal activity in biological evolution (phylogenesis), emergence of specifically human forms of activity in social history (sociogenesis), individual development throughout various phases of life (ontogenesis), appropriation of particular artefacts (instrumental genesis, Rabardel and Bourmaud, 2003), and so forth.

In activity theory development is also a research strategy. Analysis of the dynamics of how the object of study transforms over time is considered essential for a deep understanding of the object. Activity theory does not prescribe a single method of study since different types and levels of development require different methods or combinations of methods.

Dialectical logic

The developmental research perspective adopted by activity theory is often associated with dialectical logic, a concept and framework introduced by the Russian philosopher Evald Ilyenkov (Ilyenkov 2008; see Engeström et al., 1999). Dialectical logic is different from traditional formal logic in how it views contradictions and development. Traditional logic invariantly considers contradictions as indicators of problems that need to be addressed. Contradictions are to be eliminated in order to create a perfectly logical system (either an abstract one, such as a model or theory, or more concrete one, such as the management structure of an organization). In addition, traditional logic is typically not concerned with development; perfectly logical systems do not need to be changed and may stay as they are indefinitely.

Dialectical logic starts from a different assumption. It is assumed that dialectical development-that is, development driven by contradictions-is a fundamental aspect of all imaginable objects of study and therefore should be taken into consideration in analysis. While some “superficial” contradictions can be eliminated in a relatively straightforward way, there are also other, deeper contradictions which cannot be simply resolved once and for all. Any solution intended to resolve such contradictions is temporary, for it gives rise to new contradictions. An example of a contradiction of this type, well known to HCI researchers, is the contradiction between tasks and artefacts. The notion of “task-artefact cycle” (Carroll, 1991) implies that the ultimate balance between tasks and artefacts cannot be achieved. A new artefact changes the task for which it is developed which means that another artefact needs to be developed to support the new task, and so on and so forth.

Dialectical logic posits that analysis of the object of study which only deals with how the object exists at the present time is insufficient. Instead, analysis of the developmental trajectory of the object-preferably, starting from an initial undeveloped form (i.e., a “germ”)-is claimed to be critically important for understanding how the object has come to be what it is, and what contradictions can be expected to drive its further development.

The principles of activity theory, described above, comprise an integrated system: they represent different aspects of human activity as a whole. Systematic application of any of the principles often makes it necessary to eventually engage the others as well. For instance, analysis of the effects of certain technologies on human cognition from an activity theoretical perspective would require identifying the variety of activities, as well as their respective objects within which the technologies are being employed (object-orientedness), the role and place of the technologies in the hierarchical structure of each of these activities (hierarchical structure), how the activities are being re-shaped by using the technologies as mediating means (mediation), and how transformations of external components of activity are related to corresponding changes of internal components (externalization and internalization). And all these phenomena should be analysed as they unfold over time (development).

16.3.3 Engeström's activity system model

Leontiev’s approach is predominantly concerned with activities of individual human beings. While Leontiev explicitly mentions that activities can be carried out not only by individual human beings but also by social entities (collective subjects), too, he does not systematically explore the structure and development of collective activities and does not present a conceptual model of collective activity (which can probably be explained, at least partly, by the ideology-related limitations and constraints that were imposed on studies of social phenomena in the USSR). A model of collective activity, the “activity system model” (a.k.a. “Engeström’s triangle”) was proposed by the Finnish educational researcher Yrjö Engeström (1987). The model is a result of a two-step extension of Leontiev’s original concept of activity— that is, activity understood as the “subject-object” interaction — to the case of collective activity.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation).

Figure 16.10: Three-way (mediated) interaction between subject, object, and community (adapted from Engeström, 1987)

The first step, the most significant revision of Leontiev’s notion of activity as the “subject-object” interaction, was adding a third node, “community”, which resulted in a structure comprising a three-way interaction between “subject”, “object”, and “community”. This structure can be represented as a down-pointing triangle (see Figure 10). Second, it was suggested that each of the three particular interactions within the structure is mediated by a special type of meditational means. Concrete mediational means for these interactions, according to Engeström, are: (a) tools/ instruments for the “subject - object” interaction (as also posited by Leontiev), (b) rules for the “subject - community” interaction, and (c) division of labour for the “community - object” interaction. In addition, the model includes the outcome of the activity system as a whole: a transformation of the object produced by the activity in question into an intended result, which can be utilized by other activity systems. The complete model is shown in Figure 11.

As an example, consider the activity of an interaction designer who works as a member of a design team on redesigning the user interface of a computer application. The object of the activity is the existing interface, and the expected outcome is a new interface. The interaction designer employs a variety of tools in her work on the object, including physical objects (e.g., computers), software (e.g., development environments), and methods and techniques (e.g., personas). The community comprises other members of the team: interaction designers, the project manager, technicians, etc. The interaction designer’s relation with the community is mediated by explicit and implicit rules, e.g., taking part in project meetings, receiving certain financial rewards, etc. Furthermore, producing the outcome of the activity system as a whole, a new interface, is the responsibility of the entire design team: the effort of the interaction designer is a part of a larger effort of the team. Therefore, the work of the interaction designer needs to be coordinated with the work of other team members. This coordination is achieved by employing a division of labour, which thus mediates the relation between the design team and its object.

When studying complex real-life phenomena, applying one activity system model is often not sufficient. Such phenomena need to be represented as networks of activity systems. For instance, redesigning the user interface of a computer application can be a part of an even larger-scale effort, involving several design teams, directed at developing a new version of the computer application in question. Redesigning the user interface in that case would provide a partial outcome which would need to be integrated with outcomes of other activity systems (e.g., a team developing new functionality of the product) to achieve the overarching purpose of a network of activity systems.

A key tenet of Engeström’s framework is that activity systems are constantly developing. The development is understood in a dialectical sense as a process driven by contradictions. Engeström identifies four types of contradictions in activity systems:

Primary contradictions are inner contradictions of each of the nodes of an activity system. For instance, the mediating means used by a physician include various medications which, on the one hand, have certain medical effects, and, on the other hand, are products with associated costs, legal regulations, distribution channels, etc.

Secondary contradictions are those that arise between the nodes of an activity system. For instance, a certain type of medical treatment may be unsuitable for certain patients

Tertiary contradictions describe potential problems emerging in the relationship between the existing forms of an activity system and its potential, more advanced object and outcome. The advancement of an activity system as a whole may be undermined by the resistance to change, demonstrated by the existing organization of the activity system.

Finally, quaternary contradictions refer to contradictions within a network of activity systems, that is, between an activity system and other activity systems involved in the production of a joint outcome.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation).

Figure 16.11: Engeström’s activity system model

The activity system model has been employed in a range of disciplines, especially education and organizational learning (see, e.g., CRADLE, 2011).

16.3.4 Current diversity of activity theoretical frameworks

The approaches developed by, respectively, Leontiev and Engeström are currently the most common variants of activity theory. The approaches provide complementary perspectives on human activities. Leontiev’s variant mostly focuses on individuals understood as social creatures acting in social contexts. Engeström’s activity system model, on the other hand, is predominantly concerned with collective activities carried out by groups and organizations and implemented through contributions—i.e., actions—of individual subjects.

In addition, a number of other current frameworks are partly influenced by activity theory and partly built upon other approaches. Such frameworks include, for instance, instrumental genesis (Rabardel and Bourmaud, 2003), genre tracing (Spinuzzi, 2003), and the systemic-structural activity theory (Bedny and Harris, 2005; Bedny and Karwowski, 2003).

16.4 Activity theory in HCI and interaction design

16.4.1 Activity theory as a second-wave, post-cognitivist HCI theory

The dominant paradigm in HCI when it appeared as a field in early 80s was information processing (“cognitivist”) psychology. But the HCI community gradually came to realize that the focus on information processing was not sufficient. Individuals’ interests, needs, frustrations, and so forth, proved to be important and powerful factors in choosing, learning, and using a technology. Furthermore, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the use of technology critically depends on complex, meaningful, social, and dynamic contexts in which it takes place. The inner logic of the development of the field required that the scope of HCI be expanded to include the issues of motivation, meanings, culture, and social interactions. However, the cognitivist approach could not provide conceptual tools for dealing with such issues. When the limitations of the information processing psychology in HCI became widely acknowledged (Carroll, 1991), activity theory was identified as a potential alternative theoretical foundation for the field (Bødker, 1991).

The impact of activity theory on HCI and interaction design in the last two decades has been, essentially, threefold. First, the theory offered some general theoretical insights that resonated with the need for a richer conceptual framework which would allow the field to move from the “first-wave HCI” to the “second-wave HCI” (see Cooper and Bowers, 1995). Second, it served as an analytical framework for design and evaluation of concrete interactive systems and stimulated the development of a variety of analytical tools. Third and finally, the application of the approach, especially in recent years, resulted in a number of novel systems, implementing the ideas of activity-centric (or activity-based) computing.

16.4.2 General theoretical insights

The unit of analysis proposed by activity theory, that is, “subject-object” interaction, may appear similar to the traditional focus of HCI on “human-computer” interaction. However, adopting an activity theoretical perspective had important implications for understanding how people use interactive technologies. First of all, it made it immediately obvious that “computer” is typically not an object of activity but rather a mediating artefact. Therefore, generally speaking, people are not interacting with computers: they interact with the world through computers. The book by Susanne Bødker, which played a key role in introducing activity theory to HCI, reflected this perspective on interactive technologies in its very title: “Through the interface: An activity-theoretical perspective on human-computer interaction” (Bødker, 1991).

Another general theoretical contribution of activity theory to HCI was placing computer use in the hierarchical structure of human activity, that is, relating the operational aspects of the interaction with technology to meaningful goals and, ultimately, needs and motives of technology users. It did not mean rejecting the formal models of users and tasks which were developed in early HCI research, but rather extending the scope of analysis beyond low-level interaction. Such an extension was considered by some researchers as perfectly consistent with the need of the field to move “from human factors to human actors” (Bannon, 1991).

Finally, adopting the conceptual framework of activity theory promised to open up new possibilities for analysing the context of technology use. As mentioned, the lack of conceptual tools for understanding context was a major limitation of the information-processing psychology in HCI. Activity theory, with its emphasis on society, culture, and development, offered a set of concepts for capturing the context of use and taking it into account in the design, evaluation, and deployment of interactive technologies. An edited collection entitled “Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction” (Nardi, 1996a) provided an in-depth exposition of a wide range of such concepts.

16.4.3 Activity theory and other 'second-wave' theories

There are both similarities and differences between activity theory and other “second-wave theories” (cf. Kaptelinin et al., 2003), such as phenomenology (Winograd and Flores, 1986; Svanaes, 2000; Dourish, 2001) and distributed cognition (Hollan et al, 2000; Rogers, 2004).

A fundamental assumption uniting most second-wave theories is that human beings cannot be understood separately from the world in which they live, act, and cognize. The need to analyse the inseparability of humans and their physical, social, and information environments is emphasized by activity theory’s notion of activity as “subject-object” interaction, phenomenology’s concept of “being-in-the-world” (Dourish, 2001), and distributed cognition’s models of the propagation of representations across the boundaries of humans and artefacts (Hollan et al., 2000; Rogers, 2004). Another key notion, common to many post-cognitivist frameworks, is that humans’ connection to the world is to a large degree determined by the artefacts used by the humans, which artefacts are variously defined in terms of mediating means (activity theory), equipment (phenomenology), or processing and transmission of information (distributed cognition and external cognition) (see also Nardi, 1996a; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006).

While similar in a number of important respects, "second-wave" theories are also different in their general perspectives on humans and human relation to the world. Phenomenology is relatively less interested in the issues of development and the social nature of human beings, compared to activity theory. For instance, the question of how “being-in-the world” comes to exist in the first place (that is, how exactly we are thrown into the world) does not seem to play a critical role in phenomenology, which is in stark contrast with the attention paid in activity theory to how subjects emerge in evolution, social history, and individual development. In addition, a systematic exploration of the social dimension of being is a relatively recent development in the phenomenological tradition (Dourish, 2001), even though the need to take it into account was already emphasized, for instance, in the foundational work of Heidegger (1962).

The distributed cognition framework, at least as it is applied in HCI, is less explicit in its general assumptions about the nature of human beings and mostly focuses on concrete problems of understanding and supporting cognitive processes distributed between people and artefacts (Rogers, 2004). It is, however, apparent that activity theory and distributed cognition substantially differ in their respective views of human agency. Human agency is a major conceptual point of departure in activity theory, while in HCI research informed by the distributed cognition framework this issue does not play a significant role.

Comprehensive analysis of similarities and differences between activity theory and other post-cognitivist approaches is a complex issue, which is beyond the scope of this chapter. Such analysis can be found elsewhere. A systematic comparison of activity theory with a variety of other approaches is conducted by Nardi (1996b) and Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006). Halverson (2002) discusses activity theory and distributed cognition as theoretical frameworks for CSCW research. Rogers (2004) provides an overview of current theoretical approaches in HCI, including activity theory, distributed cognition, and external cognition.

16.4.4 Analytical tools

Activity theory is not a “theory” in the traditional sense in which “theory” is understood in natural sciences. Activity theory does not support creating and running predictive models which would only need to be “fed” with appropriate data. Instead, it aims to help researchers and practitioners to orientate themselves in complex real-life problems, identify key issues which need to be dealt with, and direct the search for relevant evidence and suitable solutions. In other words, the key advantage of activity theory appears to be in supporting researchers and practitioners in their own inquiry-for instance, by helping to ask right questions-rather than providing ready-made answers.

A variety of analytical tools, informed by activity theory, have been proposed to support asking “the right questions” in analysis, design, and evaluation of interactive systems (Quek and Shah, 2004). Most of such tools have the format of a checklist: they are, essentially, organized lists of questions or issues that researchers or practitioners need to pay attention to in order to make sure that the most important aspects of human activity are taken into account. The choice of the checklist format is intended to help bridge the gap between theory’s high level of abstraction and the need to address concrete issues in analysis and design. Arguably, the elaborated system of concepts (and their relations) offered by activity theory can be used in HCI to better understand the role and place of concrete interactive technologies in the overall structure of purposeful, mediated, social human action. However, the framework provides a high level description, not limited to particular types of artefacts, and needs to be specifically adjusted to the requirements of HCI research and practice. Such an adjustment can, in principle, be delegated to HCI researchers and practitioners themselves, but in many cases this strategy may not be realistic since it would require considerable time and effort. Activity theory-based checklists reduce the effort associated with domain-specific adjustment of the theory by converting the organized set of concepts, offered by the theory, into a set of concrete issues and questions, specifically related to analysis and design of interactive technologies.

Different types of such checklists are based on different variants of activity theory. For instance, the Activity Checklist (Kaptelinin et al., 1999) is intended to support systematic exploration of the “space of context” in design and evaluation of interactive technologies. The overall structure of the checklist is derived from the basic principles of Leontiev’s framework. The checklist comprises four sections-Means and ends, The environment, Learning, cognition and articulation, and Development-which are produced by combining the principle of mediation with, respectively, the principles of object-orientedness, the hierarchical structure of activity, internalization/externalization, and development, The checklist was employed in a number of design and evaluation projects (see Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006).

Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (1999) introduce another analytical tool, based on a somewhat different (while partly overlapping) set of activity-theoretical concepts. The tool comprises several organized arrays of questions and issues mostly derived from Engeström’s activity system model. The basic components of the model-Subject, Object, and Community, as well as Tools, Rules, and Roles mediating the three-way interaction between the components-serve as the main rubric for issues that need to be taken into account and modeled when designing the components of a constructivist learning environment, as well as the relationship between the components. The AODM (Activity-oriented design method) approach to supporting technology-enhanced learning analysis and design, developed by Mwanza (2002) includes several lists of issues to explore, which lists mostly capitalize upon the conceptual structure provided by Engeström’s activity system model. For instance, the Eight-Step Model prescribes a sequence of analytical steps, starting from focusing on the activity system in question as a whole, then proceeding to each of the six individual nodes and, finally, analysing the outcome of the activity system.

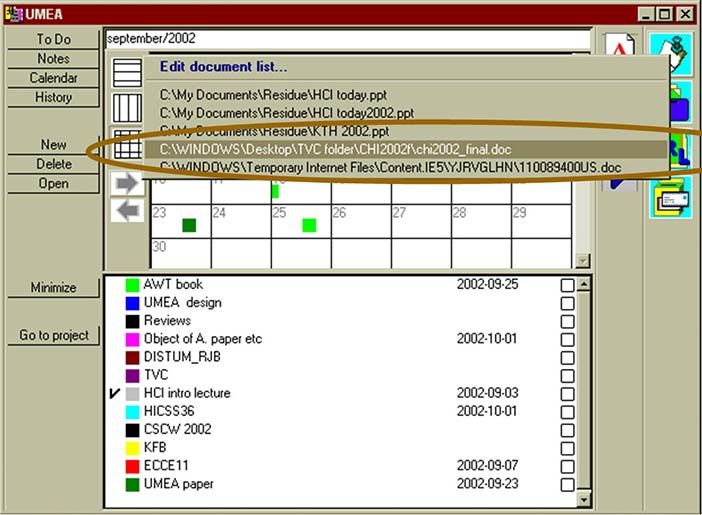

Author/Copyright holder: ACM Press. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 16.12: User interface of the UMEA system (Kaptelinin, 2003)

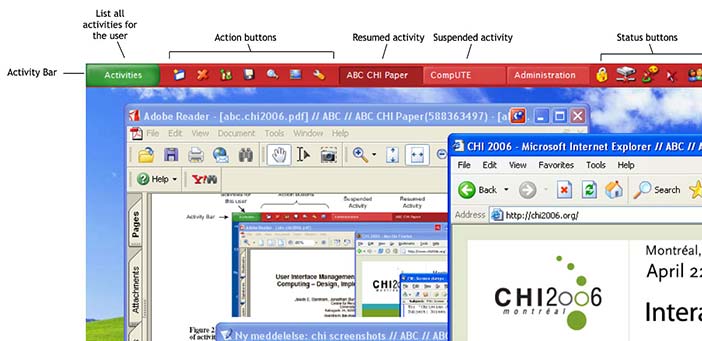

Author/Copyright holder: ACM Press. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 16.13: An overall view of the ABC user interface for Windows XP (Bardram et al., 2006)

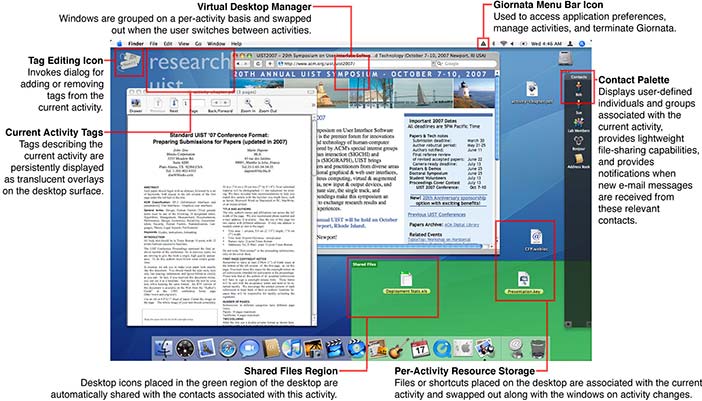

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Stephen Voida. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Figure 16.14: Giornata’s user interface

16.4.5 Activity-centric computing

Adopting an activity-theoretical perspective has an immediate implication for design: it suggests that the primary concern of designers of interactive systems should be supporting meaningful human activities in everyday contexts, rather than striving for logical consistency and technological sophistication. Currently many systems fail to comply with this, seemingly obvious, requirement. For instance, traditional desktop systems organize digital resources into formal categories (e.g., files, email messages, bookmarks...) rather than according to the relevance of a resource to the task at hand, and most systems provide limited support for task switching and interruptions (Bardram et al., 2006; Kaptelinin and Czerwinski, 2007).

Activity-centric (also referred to as "activity-centred" or "activity-based") computing is an approach to designing interactive systems according to which the top priority and an explicit aim in the design of digital artefacts and environments should be supporting meaningful human activities. The work in activity-centric computing is being conducted from a diversity of perspectives; some of the key projects (e.g., Moran et al., 2005; Moran, 2006) do not employ actvity theory as their theoretical foundation. It is fair to say, however, that the theory has influenced, one way or another, many (if not most) developments in the area.

An early attempt to propose an activity-centric alternative to then dominant application-centric and document-centric approaches was made by Don Norman and his colleagues at Apple Computer (Norman, 1998), who employed a somewhat modified version of Leontiev’s framework. More recently, Norman (2005) argues that activity-centred design has advantages over traditional human-centred design and should supersede the latter.

For various reasons, the attempt to introduce an activity-centric approach at Apple Computer has not resulted in the development of concrete novel technologies. However, in the recent decade a number of systems, adopting an activity-centric perspective and, for the most part, explicitly informed by activity theory, have been designed and implemented. They include, for instance, the UMEA system (Kaptelinin, 2003, see Figure 12), a variety of systems implementing the ABC framework, e. g. the Windows XP ABC system (Bardram et al., 2006, see Figure 13), and the Giornata system (Voida and Mynatt, 2009, see Figure 14). All these systems provide alternatives to, or extensions of, traditional desktop systems to enable organizing various digital resources, such as documents and URL’s, around higher-level, meaningful tasks of the user, defined as “projects” or “activities”. In UMEA and the Windows XP ABC system it is achieved by automatically assigning resources to the activity selected by the user, while in Giornata a virtual desktop is set up for each new activity.

The results of evaluation studies (Kaptelinin, 2003; Bardram et al., 2006; Voida and Mynatt, 2009) suggest that activity-centric systems have certain advantages over more conventional types of systems.

Search string | Number of hits | Search string | Number of hits |

phenomenology | 1,552 | phenomenology & HCI | 251 |

“activity theory” | 1,496 | ”activity theory” & HCI | 512 |

“distributed cognition” | 1,102 | “distributed cognition” & HCI | 383 |

ethnomethodology | 621 | ethnomethodology & HCI | 269 |

”situated action” | 551 | ”situated action” & HCI | 209 |

“language action” | 448 | “language action” & HCI | 66 |

“actor network theory” | 374 | “actor network theory” & HCI | 43 |

”external cognition” | 141 | “external cognition” & HCI | 60 |

Table 16.1: Second wave theories: Number of hits in the ACM Digital Library (dl.acm.org) for names of a selection of theoretical approaches used as search strings, January 2nd, 2012

16.5 Conclusions and prospects for the future

The discussion in this chapter indicates that in the last two decades, since its introduction to HCI, activity theory has established itself as a leading theoretical approach in the field. Along with some other post-cognitivist approaches, most notably distributed cognition (Hollan et al., 2000) and phenomenology (Svanaes, 2000; Dourish, 2001), it shapes the theoretical landscape of current HCI and interaction design. A number of fundamental notions, such as technological mediation, originating from activity theory have become widely accepted in the field. Table 1 gives an approximation, if very rough and imprecise, of the relative “popularity” of activity theory in studies of information technologies compared to some other theoretical approaches.

At the same time, lessons learnt from applying activity theory in HCI and interaction design indicate that the theory needs to be further developed, and there are some issues which must be addressed in the future. First, the concepts of activity theory should be more clearly specified and operationalized to make it easier for researchers and practitioners to see how the theory can be applied in concrete cases (cf. Rogers, 2004). Second, the conceptual framework of activity theory needs to be expanded to more adequately deal with coordination of multiple activities and cross-activity integration. Cross-activity integration is becoming an increasingly important issue in current uses of technology, characterized by complex social contexts (e.g., a combination of work and non-work factors typical of everyday practices of teleworkers) and employing multiple digital and non-digital technologies (or “webs of mediators” - see Bødker and Andersen, 2005). Third, as observed by Bødker (2006), HCI appears to be entering its new, third wave, during which there is a marked increase of interest in aesthetics and experience (see also Hassenzahl, 2011). The move toward third-wave HCI, according to Bødker (2006) presents a challenge for second-wave theories, including activity theory. Arguably, the conceptual apparatus of activity theory can, in principle, be employed to analyse subjective experiences, and some activity-theoretical analyses do address the issues of emotion, passion, and so forth (e.g., Vasilyuk, 1992; Nardi, 2005). However, the potential of activity theory to deal with such issues remains relatively untapped. Expanding the scope of activity-theoretical analysis in these three directions appears to be essential to make sure the theory continues to provide HCI with new insights and to help the field to deal with emerging challenges.

16.6 Where to learn more

16.6.1 Activity theory in HCI

16.6.1.1 Books

16.6.1.2 Articles and book chapters

Blackler, F. (1995): Activity theory, CSCW and organizations. In: Monk, Andrew F. and Gilbert, Nigel G. (eds.). "Perspectives on HCI: Diverse Approaches". Academic Press

Kuuti, Kari (1995): Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In: Nardi, Bonnie A. (ed.). "Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction". The MIT Presspp. 17-44

Rogers, Yvonne (2004): New Theoretical Approaches for HCI. In Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, (38) pp. 1-43

Wilson, T. D. (2008): Activity theory and information seeking. In Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 42 (1) pp. 119-161

16.6.2 Activity theory in general

16.6.2.1 Books

16.6.2.2 Online resources

The Mind, Culture, and Activity Homepage is an interactive forum for a community of interdisciplinary scholars who share an interest in the study of human mind in its cultural and historical contexts.

International Society for Cultural and Activity Research (ISCAR)

16.7 Acknowledegements

I would like to thank Mads Soegaard, Rikke Friis Dam, Klaus Bærentsen, Allan Holstein-Rathlou, Bonnie Nardi, and Dag Svanæs for their feedback, help, and support. Special thanks to Mads for providing numerous figures for this chapter

16.8 References

Bannon, Liam (1991): From human factors to human actors: the role of psychology and human-computer interaction studies in system design. In: Greenbaum, Joan and Kyng, Morten (eds.). "Design at Work: Cooperative Design of Computer Systems". Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associatespp. 25-44

Bardram, Jakob E., Bunde-Pedersen, Jonathan and Soegaard, Mads (2006): Support for activity-based computing in a personal computing operating system. In: Proceedings of ACM CHI 2006 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2006. pp. 211-220

Basov, Mikhail Ia. (1991): The Organization of Processes of Behavior (A Structural Analysis) (originally published in Russian in 1931). In Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 29 (5) pp. 14-83

Bedny, Gregory Z. and Harris, Steven Robert (2005): The Systemic-Structural Theory of Activity: Applications to the Study of Human Work. In Mind, Culture and Activity, 12 (2) pp. 128-147

Bedny, Gregory and Karwowski, Waldemar (2003): A Systemic-Structural Activity Approach to the Design of Human-Computer Interaction Tasks. In International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 16 (2) pp. 235-260

Bertelsen, Olav W. and Bødker, Susanne (2003): Activity Theory. In: Carroll, John M. (ed.). "HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks". San Francisco: Morgan Kaufman Publisherspp. 291-324

Blackler, F. (1995): Activity theory, CSCW and organizations. In: Monk, Andrew F. and Gilbert, Nigel G. (eds.). "Perspectives on HCI: Diverse Approaches". Academic Press

Brushlinsky, Andrej V. and Aboulhanova-Slavskaya, Ksenia A. (2000): The historical context and modern denotations of the fundamental work by S. L. Rubinshtein. Afterword to the 4th edition of Foundations of General Psychology (in Russian). In: Rubinstein, Sergey L. (ed.). "Foundations of General Psychology - 4th edition". St. Petersburg, Russia: Piter

Bødker, Susanne (2006): When second wave HCI meets third wave challenges. In: Proceedings of the Fourth Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 2006. pp. 1-8

Bødker, Susanne (1989): A Human Activity Approach to User Interfaces. In Human-Computer Interaction, 4 (3) pp. 171-195

Bødker, Susanne (1991): Through the Interface - A Human Activity Approach to User Interface Design. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Bødker, Susanne and Andersen, Peter B. (2005): Complex Mediation. In Human-Computer Interaction, 20 (4) pp. 353-402

Carroll, John M. (ed.) (1991): Designing Interaction: Psychology at the Human-Computer Interface. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press

Carroll, John M. (2013). Human Computer Interaction - brief intro. Retrieved 4 November 2013 from [URL to be defined - in press]

Cole, Michael and Engeström, Yrjö (1993): A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. In: Salomon, Gavriel (ed.). "Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives)". Cambridge University Press

Cooper, Geoff and Bowers, John (1995): Representing the user: notes on the disciplinary rhetoric of human-computer interaction. In: Thomas, Peter J. (ed.). "The Social and Interactional Dimensions of Human-Computer Interfaces (Cambridge Series on Human-Computer Interaction)". Cambridge University Press

CRADLE (2011). CRADLE, Center for Research on Activity, Development and Learning. Retrieved 19 April 2011 from CRADLE: http://www.helsinki.fi/cradle/

Cypher, Allen (1986): The structure of users' activities. In: Norman, Donald A. and Draper, Stephen W. (eds.). "User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction". Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associatespp. 243-264

Daniels, Harry, Edwards, Anne, Engeström, Yrjö, Gallagher, Tony and Ludvigsen, Sten R. (eds.) (2009): Activity Theory in Practice: Promoting Learning Across Boundaries and Agencies. Routledge

Dourish, Paul (2001): Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. MIT Press

Engeström, Yrjö (1987): Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research.Orienta-Konsultit Oy

Engeström, Yrjö (ed.) (1990): Learning, Working and Imagining. Orienta-Konsultit Oy

Engeström, Yrjö, Miettinen, Reijo and Punamaki, Raij (eds.) (1999): Perspectives on Activity Theory (Learning in Doing Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives). Cambridge University Press

Gay, Geraldine and Hembrooke, Helene (2004): Activity-Centered Design: An Ecological Approach to Designing Smart Tools and Usable Systems (Acting with Technology). The MIT Press

Halverson, Christine (2002): Activity Theory and Distributed Cognition: Or What Does CSCW Need to DO with Theories?. In Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 11 (1) pp. 243-267

Hassenzahl, Marc (2011). User Experience and Experience Design. Retrieved 4 November 2013 from [URL to be defined - in press]

Heidegger, Martin (1962): Being and Time. English translation 1962.

Hollan, James D., Hutchins, Edwin and Kirsh, David (2000): Distributed Cognition: Toward a New Foundation for Human-Computer Interaction Research. In ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7 (2) pp. 174-196

Ilyenkov, E. V. (2008): Dialectic Logic: Essays on Its History and Theory. Aakar Books

Jonassen, David H. and Rohrer-Murphy, Lucia (1999): Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments. In Educational Technology Research & Development, 47 (1) pp. 61-79

Kaptelinin, Victor (2003): UMEA: translating interaction histories into project contexts. In: Cockton, Gilbert andKorhonen, Panu (eds.) Proceedings of the ACM CHI 2003 Human Factors in Computing Systems ConferenceApril 5-10, 2003, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, USA. pp. 353-360

Kaptelinin, Victor and Czerwinski, Mary (2007): Introduction. In: Kaptelinin, Victor and Czerwinski, Mary (eds.). "Beyond the Desktop Metaphor: Designing Integrated Digital Work Environments". The MIT Press

Kaptelinin, Victor and Nardi, Bonnie A. (2006): Acting with Technology: Activity Theory and Interaction Design.The MIT Press

Kaptelinin, Victor and Nardi, Bonnie A. (2012): Activity Theory in HCI: Fundamentals and Reflections. Morgan and Claypool

Kaptelinin, Victor, Nardi, Bonnie A. and Macaulay, Catriona (1999): Methods & tools: The activity checklist: a tool for representing the. In Interactions, 6 (4) pp. 27-29

Kaptelinin, Victor, Nardi, Bonnie A., Bødker, Susanne, Carroll, John M., Hollan, James D., Hutchins, Edwin andWinograd, Terry (2003): Post-cognitivist HCI: second-wave theories. In: Cockton, Gilbert and Korhonen, Panu (eds.) Extended abstracts of the 2003 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI 2003 April 5-10, 2003, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, USA. pp. 692-693

Koschmann, Timothy, Kuutti, Kari and Hickma, Larry (1998): The Concept of Breakdown in Heidegger, Leont'ev, and Dewey and Its Implications for Education. In Mind, Culture, and Activity, 5 (1) pp. 25-41

Leontiev, Aleksei Nikolaevich (1981): Problems of the development of the mind (originally published in Russian in 1959). Moscow, Russia, Progress

Leontiev, Aleksei Nikolaevich (1978): Activity, consciousness, and personality (originally published in Russian in 1975). Prentice-Hall

Leontyev, Aleksei N. (1978): Activity, consciousness, and personality. Pergamon Press

Mescherjakov, Boris and Zinchenko, Vladimir P. (eds.) (2003): Big Psychological Dictionary (in Russian). Prime-Evroznak

Moran, Thomas P. (2006): Activity: Analysis, Design, and Management. In: Bagnara, Sebastiano and Smith, Gillian Crampton (eds.). "Theories and Practice in Interaction Design (Human Factors and Ergonomics Series)". Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Moran, Thomas P., Cozzi, Alex and Farrell, Stephen P. (2005): Unified activity management: supporting people in e-business. In Communications of the ACM, 48 (12) pp. 67-70

Mwanza, Daisy (2002): Conceptualising work activity for CAL systems design. In J. Comp. Assisted Learning, 18 (1) pp. 84-92

Nardi, Bonnie A. (ed.) (1996a): Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction.MIT Press

Nardi, Bonnie A. (1996b): Studying context: A comparison of activity theory, situated action models, and distributed cognition. In: Nardi, Bonnie A. (ed.). "Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction". MIT Press

Nardi, Bonnie A. (2005): Objects of desire: Power and passion in collaborative activity. In Mind, Culture, and Activity, 12 pp. 37-51

Norman, Donald A. (2005): Human-centered design considered harmful. In Interactions, 12 (4) pp. 14-19

Norman, Donald A. (1998): The Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer Is So Complex and Information Appliances Are the Solution. MIT Press

Quek, Amanda and Shah, Hanifa (2004): A Comparative Survey of Activity-Based Methods for Information Systems Development. In: ICEIS 2004 2004. pp. 221-232

Rabardel, Pierre and Bourmaud, Gaetan (2003): From computer to instrument system: a developmental perspective. In Interacting with Computers, 15 (5) pp. 665-691

Rogers, Yvonne (2004): New Theoretical Approaches for HCI. In Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, (38) pp. 1-43

Rubinshtein, Sergey L. (1986): The principle of creative self-activity (on the philosophical foundations of modern pedagogy). Originally published in 1922 in Russian. In Voprosy Psikhologii, 4 pp. 101-107

Rubinshtein, Sergey L. (1946): Foundations of General Psychology. Second edition. (in Russian). Moscow, Russia, Uchpedgiz

Spinuzzi, Clay (2003): Tracing Genres through Organizations: A Sociocultural Approach to Information Design (Acting with Technology). The MIT Press

Svanaes, Dag (2000): Understanding Interactivity: Steps to a Phenomenology of Human-Computer Interaction.Trondheim, Norway, Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet (NTNU)

Vasilyuk, Fyodor (1992): The Psychology of Experiencing: The Resolution of Life's Critical Situations (originally published in Russian in 1984). New York University Press

Voida, Stephen and Mynatt, Elizabeth D. (2009): It feels better than filing: everyday work experiences in an activity-based computing system. In: Proceedings of ACM CHI 2009 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2009. pp. 259-268

Voida, Stephen, Mynatt, Elizabeth D. and Edwards, W. Keith (2008): Re-framing the desktop interface around the activities of knowledge work. In: Cousins, Steve B. and Beaudouin-Lafon, Michel (eds.) Proceedings of the 21st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology October 19-22, 2008, Monterey, CA, USA. pp. 211-220

Vygotsky, Lev (1978): Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press

Wertsch, James V. (1981): The concept of activity in Soviet psychology: An introduction. In: Wertsch, James V. (ed.). "The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology". M.E. Sharpe

Winograd, Terry and Flores, Fernando (1986): Understanding Computers and Cognition. Norwood, NJ, Intellect