Accessibility: Usability for all

- 863 shares

- 2 years ago

Design for All is a concept that describes a wide range of design approaches, methods, techniques and tools for designers to meet the vast diversity of users’ needs and requirements. Designers strive to build access features into products from the start of their design process.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Design for All emerged in human-computer interaction (HCI) literature in the late 1990s, after a series of research efforts that the European Commission mainly funded. The concept comes from the combination of three other vital areas of user experience (UX) design:

UCD stresses that the quality of use of a system, including its usability and other factors, depends on the nature of the users, tasks, contexts and more. As such, it’s a design process that values a multidisciplinary and user-geared perspective. However, its scope is limited in how it can handle the sheer diversity of user needs. Also, designers have little guidance on how to address the requirements of radically different user groups.

Accessibility involves the availability of alternative devices and interaction styles. Traditionally, the focus was on enabling users with disabilities to access websites and applications designed for users without disabilities. This was achieved through assistive technologies designed to “decode” the experience appropriately for users with specific disabilities. However, assistive technologies are essentially reactive in nature, and they only adapt “non-disability-oriented” experiences for these users. Also, with the rapid pace of technological developments, it has become increasingly difficult to develop accessibility add-ons. Moreover, there is a new focus on people at risk of technological exclusion, and it’s not just limited to users with disabilities. So, designing for all is about integrating accessibility early on in the design process. This means you have to “bake” it in from the early stages, not come back to it as if it were some afterthought to retrofit following a “mainstream” release.

With its emphasis on designing one product (per project) that everyone can use, universal design offers great promise to “level the playing field” so all users can access products. A classic example is the curb cut for wheelchair users and anyone else who may need a ramp, such as if they have a bicycle.

When you’re designing applications and websites, you can leverage universal design through, for example, subtitles. Subtitles help hard-of-hearing as well as non-native-English speakers, plus any user in a noisy environment. However, universal design typically involves physical rather than digital products. That’s where design for all comes in.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Design for all shares common objectives with two related approaches: universal design and inclusive design. However, they each approach the goal of user inclusivity and removing barriers from slightly different angles. The differences lie primarily in their scope and the specific user needs they address.

Here, you aim to create products and environments that are inherently accessible to both people without disabilities and people with disabilities. It is broader in scope than design for all as it encompasses physical spaces and products, not just digital interfaces. Yet it is narrower in scope in the sense that there is just one design to fit everyone. So, it cannot account for the sheer breadth of human diversity required for every problem imaginable.

With this approach, you strive particularly to include and learn from a diverse range of users during the design process. It shares many similarities with design for all. However, it’s more explicit in terms of how it actively involves traditionally underrepresented user groups in the design process.

Design for All’s inclusive approach caters to the needs of all users, whatever their abilities or disabilities. It aims to remove barriers and offer equal access to everyone. As such, it encompasses various dimensions of diversity, including:

Perception – Blindness, deafness, etc.

Motion – Physical disabilities that include quadriplegia, loss of limbs, arthritis, neuropathy, weakness in hands, among others.

Cognition – Differences in brain functions that arise from a variety of factors, including brain injury, stroke, Alzheimer’s, and mental illness, and often referred to as neurodiversity.

The BBC has been a long-term champion of designing for all, building accessible features into its new site and more.

© BBC, Fair Use

The Digital Age has witnessed a phenomenon at both extremes of the generation gap. Children are more computer-literate and from an earlier age. However, they still have user needs as children, no matter how more advanced they may become compared to previous generations. Similarly, older users, who came of age before the advent of home computers and the internet, will have different ability-related requirements. Compounding this is the demographic shift in the developed world with large aging populations in many countries.

Gearing a product to an English-speaking market may restrict it culturally. While English is the most common language spoken in the world, it accounts for roughly 20% of the world’s population. That means a whopping 80% of users from outside the English-speaking world may miss messages because these get lost in translation. Plus, different cultures interpret symbols, colors, gestures, etc. differently. You as a designer therefore need to be sensitive to these issues and look into localization that goes beyond just translation. Designing for all is an approach to recognize, appreciate and integrate these differences rather than neutralize them with a one-size-fits-all mentality.

Cochrane Library is a collection of databases that contain high-quality, independent evidence to inform healthcare decision-making. Cochrane’s global volunteers help the organization offer translations of its evidence-based research in several languages.

© John Wiley and Sons Inc, Fair Use

Poverty, social status and limited educational opportunities are serious barriers to many potential users across the world. Design for All offers a guiding light to remind designers to address the situation by using their education and skills to create designs that are accessible to people whose own education and skills are below the levels many designers might otherwise assume.

Wider Audience Reach: By ensuring that your product or service is accessible and usable by all, you widen your audience reach. This can lead to increased user engagement, customer satisfaction, and ultimately, business growth.

Improved User Experience: Designing for all can lead to better user experiences for everyone, not just those with disabilities. By considering the needs of a diverse range of users, you can create products that are more intuitive, efficient, and enjoyable to use.

Innovation: Designing for all can spur innovation. When designers are challenged to create solutions that cater to a diverse range of users, they often come up with innovative ideas that improve the overall design of the product.

Social Responsibility: Designing for all reflects a commitment to social responsibility. It shows that a company values all its users and is committed to providing equal access to its products and services.

An Oxford University study investigates how mobile phones empower women in developing nations. Consider the needs of all your users in your design process—whether it is a physical product or a digital service.

© The University of Oxford, Fair Use

Complexity: Designing for all can be complex. It requires a deep understanding of diverse user needs, abilities, and preferences. It also demands a high level of creativity and problem-solving skills to come up with design solutions that cater to a wide range of users.

Resource Intensive: Designing for all can be resource-intensive. It may require more time, effort, and money to research, design, test, and iterate on solutions that are accessible and usable by all.

Difficulty in Measuring Success: Measuring the success of design for all can be challenging. It's not always easy to quantify the impact of inclusive design practices and to demonstrate their value to stakeholders.

UserWay is a digital accessibility provider that helps websites be accessible. The organization “walks the talk” by offering multiple options to view their content, embodying the principles of designing for everyone.

© UserWay, Fair Use

It’s essential to adapt the adage “know your users” to ensure that you know the diversity of your users. Here is a list of design methods you can adapt with careful consideration to ensure your design encompasses the most diverse range of user characteristics and needs. And these show you how you can fine-tune them to help make your design truly accessible to all.

View users as they conduct an activity you want to investigate, and record your observations and insights. Your goal is to gain insights into the user experience as the users experience and understand it within the context of use.

Use quantitative and qualitative UX research methods where you can carefully design questions so that users can give you meaningful answers. The questions must be relevant and focused to prevent irrelevant responses.

Conduct interviews (ideally semi-structured ones), with a series of questions with enough scope for users to expand on their answers.

Provide research participants with diaries and probes to collect data and gather insights from a variety of users. Participants keep self-reported records of their activities over a period of time. These can expose patterns of behavior you might otherwise miss in short-term observation. These materials can help expose user needs, although they require careful planning to maximize user trust, comfort and accuracy of answers.

These include brainstorming with participants from different stakeholder groups who have good communication abilities and skills. A small group of users with special needs is more likely to be open to participate than a single interviewee alone. Such discussions can yield vital insights about diversity and special needs of users.

You put yourself in the position of a user with a disability. For example, earplugs help you simulate hearing loss. This can bring important considerations and insights to the design table.

Apple is an industry leader in designing for all, building for a huge expanse of diverse user needs. Alt Text:

© Apple, Fair Use

Scenarios: Use narrative descriptions of interactive processes, including user and system actions, to show how users may execute tasks in certain contexts.

Storyboards: Use a graphical depiction of scenarios in sequences of images to show the relationship between user inputs and system outputs.

Personas: Create a model of a user, complete with name, personality and picture, to represent each of the most important user groups.

Use a concrete representation of part or all of an interface. It can be low-, mid- or mixed-fidelity, ideally low for starting with. You can tailor these to suit aspects of your system that you want to investigate and test. The earlier you do it, the more insights you can yield from a diverse range of potential users. Prototypes are especially helpful for users with disabilities, as they have something concrete before them. This can save greatly on costs later, since it can reveal essential limitations about your original ideas for a product.

Test on a diverse range of “real users” as they follow a set of tasks. Here’s where you evaluate the usability of your design. It’s also where, especially with early designs and prototypes, you can gain precious insights into diverse user requirements. It’s important to design these tests thoughtfully, be they remote or in-person, so the insights reflect what users actually do, not what they claim to do.

Get the full involvement of users through a variety of techniques, such as brainstorming, scenario building, sketching, storyboarding and interviews. This active partnership with users brings them on board and helps guide your design process from early on.

© Margherita Antona, Stavroula Ntoa, Ilia Adami and Constantine Stephanidis, Fair Use

Here are some of our top tips for implementing Design for All in your design process:

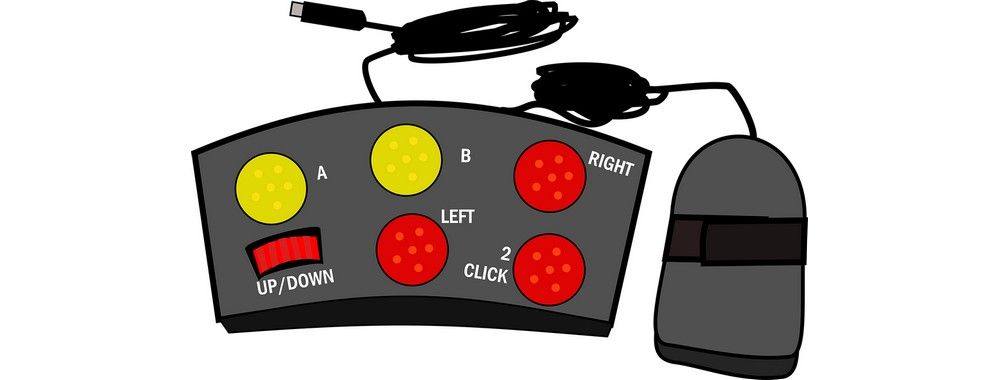

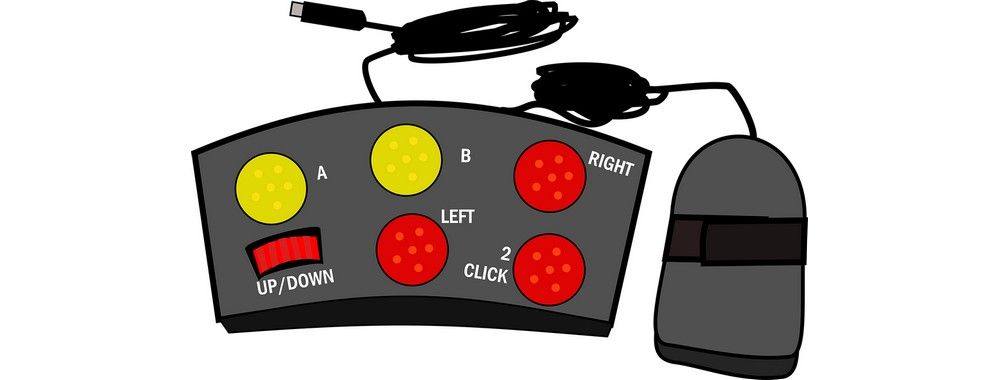

Provide multiple ways for users to interact with your product or service. This could include different input methods (e.g., touch, voice, keyboard), different output methods (e.g., visual, auditory, haptic), and different ways of navigating and accessing content.

Design your product or service to be flexible and adaptable to different user needs and preferences. This could include customizable settings, adjustable interface elements, and adaptive content.

Follow established accessibility standards and guidelines, such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) for web design.

Mainstream design is catching up with traditionally ignored user communities and still has a long way to go. Stay updated with research and industry best practices and pursue research independently if the existing research is inadequate.

As with everything in design, iterate to incorporate user feedback and new research.

Google incorporates principles of Design for All and offers guidance on creating accessible and inclusive digital experiences. The company continuously updates its Material Design guidelines to cater to wider audiences. Here, for example, is the announcement for new typefaces for legibility and lesser-served languages.

© Google, Fair Use

Remember, Design for All is not just a trend or a nice-to-have; it's a necessity for creating products and services that truly meet the needs of all users. And designing for all is not just about meeting legal requirements or checking off boxes on an accessibility checklist. It's about embracing diversity, promoting inclusivity, and building empathy in design. It challenges you to think beyond your assumptions and biases as a designer, to design products that are truly able to reach all people, and which all people can use and enjoy. The results are more intuitive, efficient, user-friendly and enjoyable products for everyone.

Here’s the entire UX literature on Design for All by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Design for All with our course Accessibility: How to Design for All .

Good accessibility is crucial to making your website or app a success. Not only is designing for accessibility required by law in many countries—if you fail to consider accessibility, you are excluding millions of people from using your product. The UN estimates that more than 1 billion people around the world live with some form of disability and as populations age over the coming years, that number is expected to rise rapidly. Add to that the 10 percent of people who suffer from color blindness, and you start to get an idea of why accessibility is so important—not just for moral and legal reasons, but also so that your products can reach their full potential. You need to design for accessibility!

So… what is a proven and pain-free way to well-executed accessibility? If you’ve ever tried to optimize your site or app for accessibility, you’ll know it can be a complex and intimidating task… and it can therefore be very tempting to leave it until last or, worse still, avoid it altogether. By understanding that accessibility is about more than just optimizing your code, you’ll find you can build it into your design process. This will ensure you are taking a disability advocacy approach, and keeping the focus on your users throughout the development process.

This course will help you achieve exactly that—from handling images to getting the most out of ARIA markup, you’ll learn how to approach accessibility from all angles. You’ll gain practical, hands-on skills that’ll enable you to assess and optimize for common accessibility issues, as well as show you how to place an emphasis on the quality of the user experience by avoiding classic mistakes. What’s more, you’ll also come away with the knowledge to conduct effective accessibility testing through working with users with disabilities.

The course includes interviews with an accessibility specialist and blind user, as well as multiple real-world examples of websites and apps where you can demonstrate your skills through analysis and accessibility tests. Not only will this give you a more practical view of accessibility, but you’ll also be able to optimize your websites and mobile apps in an expert manner—avoiding key mistakes that are commonly made when designing for accessibility.

You will be taught by Frank Spillers, CEO of the award-winning UX firm Experience Dynamics, and will be able to leverage his experience from two decades of working with accessibility. Given that, you will be able to learn from, and avoid, the mistakes he’s come across, and apply the best practices he’s developed over time in order to truly make your accessibility efforts shine. Upon completing the course, you will have the skills required to adhere to accessibility guidelines while growing your awareness of accessibility, and ensuring your organization’s maturity grows alongside your own.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help democratize design knowledge!